The nuclear family, traditionally defined as parents and their children, has been a cornerstone of societal structure. However, critics like David Brooks argue it has become isolating, fostering dependency and pressure on individual households, as highlighted in discussions about its evolution and challenges.

Definition and Evolution of the Nuclear Family

The nuclear family is defined as a household consisting of two parents and their children, emphasizing a core unit separate from extended relatives. This structure emerged as a dominant model in the mid-20th century, particularly in Western societies, and was often idealized as the foundation of social stability. However, critics argue that its rise has led to isolation and pressure on individual households. The term “nuclear” highlights its focus on the immediate family, contrasting with extended family systems. Over time, the nuclear family has faced criticism for its limitations, including economic strain and lack of support. David Brooks and others contend that this model has become unsustainable, arguing that its emphasis on self-sufficiency has led to societal challenges. The nuclear family’s evolution reflects broader shifts in cultural values and economic conditions.

Cultural and Historical Context of the Nuclear Family Model

The nuclear family model has deep historical and cultural roots, often tied to Western societal values and religious traditions. It emerged as a response to the needs of industrialized societies, emphasizing self-sufficiency and privacy. The model was idealized in the mid-20th century, particularly in post-World War II America, where it became a symbol of stability and prosperity. Culturally, it was portrayed as the optimal structure for raising children, with a breadwinning father and a homemaking mother. However, critics argue that this model was overly rigid and ignored the benefits of extended family support. The nuclear family was also seen as a way to promote individual autonomy, but it often led to isolation, as families became disconnected from broader community networks. This cultural ideal has been challenged for its limitations in providing emotional and practical support, leading to calls for more inclusive family structures.

Historical Context and Rise of the Nuclear Family

The nuclear family emerged as a dominant structure in the mid-20th century, symbolizing stability and prosperity in post-war America, but its rise also sparked critiques of isolation and disconnection.

The Emergence of the Nuclear Family in the Mid-20th Century

The mid-20th century saw the nuclear family rise as a cultural ideal, symbolizing post-war prosperity and stability. Suburbanization and economic growth enabled families to live independently, reducing reliance on extended kin. This shift was bolstered by policies favoring homeownership and traditional gender roles, creating a homogeneous vision of family life. Sociologists like Eugene Litwak noted that while nuclear families appeared self-sufficient, they were often part of informal networks, challenging the notion of complete autonomy. Critics argue this structure isolated families, fostering financial and emotional strain. The nuclear family’s dominance coincided with a decline in community support systems, highlighting its limitations in providing comprehensive care for children and vulnerable members. This period set the stage for later critiques of the nuclear family as a potentially harmful ideal.

Societal Factors Contributing to Its Dominance

The nuclear family’s dominance in the mid-20th century was fueled by post-war economic prosperity and suburbanization, enabling families to live independently. Media and advertising idealized this structure, promoting it as the norm. Traditional gender roles, with men as breadwinners and women as homemakers, further solidified its place. Government policies, such as tax incentives for homeownership, also supported this model. The decline of extended family support systems and communal living made nuclear families appear self-sufficient. These factors created a cultural narrative that equated nuclear families with stability and success, shaping societal expectations and norms. However, this dominance also fostered isolation, as families relied less on community support, highlighting the limitations of this structure in addressing modern challenges.

Policy Influences on the Adoption of the Nuclear Family Structure

Government policies and legal frameworks significantly influenced the adoption of the nuclear family structure. Tax incentives, housing subsidies, and social security programs often favored nuclear families, reinforcing their dominance. Legal definitions of “family” frequently excluded extended relatives, further entrenching the nuclear model. Post-war policies, such as the GI Bill, provided benefits that encouraged suburban homeownership, ideal for nuclear families. Additionally, immigration laws and welfare systems often prioritized nuclear family units, marginalizing alternative structures. These policies created a societal expectation that nuclear families were the ideal and most supported form of family life. Over time, this institutional backing solidified the nuclear family’s role, often at the expense of more communal or extended family systems, contributing to their decline in modern societies.

Decline of the Nuclear Family Model

The nuclear family model has declined due to economic pressures, shifting social norms, and criticism of its isolating nature, as highlighted in discussions about its shortcomings.

Shifts in Social Norms and Values

Changing social norms and values have significantly contributed to the decline of the nuclear family model. The rise of single-parent households, blended families, and same-sex parent families reflects evolving societal acceptance of diverse family structures. Increased divorce rates, women’s liberation, and shifting gender roles have also played a role. Many now view the nuclear family as an outdated ideal, emphasizing instead the importance of emotional and financial support over traditional structures. These shifts highlight a broader societal movement toward inclusivity and recognition of varied family dynamics, challenging the historical dominance of the nuclear family model.

Impact of Economic Pressures on Family Structures

Economic pressures have significantly influenced the decline of the nuclear family model; Rising costs of living, wage stagnation, and the erosion of social safety nets have made it increasingly difficult for two-parent households to thrive. Many families face financial strain, leading to stress and instability. The shift toward dual-income households has also blurred traditional roles, with both parents working to make ends meet. Additionally, economic challenges have forced families to seek alternative structures, such as blended or single-parent households, to cope with financial demands. These pressures highlight the vulnerability of the nuclear family model in modern economic conditions, pushing families to adapt and redefine their structures for survival.

Changing Roles of Women and Gender Dynamics

The rise of feminism and women’s increasing participation in the workforce have significantly altered traditional gender roles within families. Women are no longer confined to domestic duties, leading to a redefinition of family dynamics. This shift has challenged the nuclear family model, where men were often the sole breadwinners and women managed household responsibilities. Modern families now embrace shared responsibilities, with both partners contributing financially and domestically. However, this transition has also introduced challenges, such as balancing work and family life, which can lead to stress and tension. The evolving roles of women have further highlighted the limitations of the nuclear family structure, as it often fails to accommodate the diverse needs of contemporary society. This shift underscores the need for more flexible and inclusive family models to reflect changing gender dynamics and societal expectations.

Comparison Between Nuclear and Extended Family Structures

Nuclear families, consisting of parents and children, are often isolated, while extended families provide broader support networks and shared responsibilities, fostering mutual dependence and community ties.

Historical Prevalence of Extended Families

Extended families, comprising multiple generations and relatives, have historically been the norm in many cultures. Unlike nuclear families, they provided shared resources, childcare, and emotional support. Sociologist Eugene Litwak described extended families as a “coalition of nuclear families” in mutual dependence. This structure was common before the rise of urbanization and industrialization, which eroded traditional family networks. In feudal societies, extended families were essential for economic survival, with grandparents, aunts, and uncles contributing to household duties. Christianity also reinforced extended family ties, emphasizing communal living and intergenerational responsibility. However, the shift to nuclear families in the mid-20th century, driven by modernization, weakened these bonds, leaving many families isolated. This historical contrast highlights the decline of collective family support systems, a key theme in critiques of the nuclear family model. Extended families, while less prevalent today, remain vital in many non-Western cultures.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Each Structure

Nuclear families offer autonomy and mobility, ideal for modern societies, but often lack support systems. Extended families provide emotional and financial backing, fostering resilience, yet may limit individual freedom. The nuclear model, while promoting independence, can isolate families, making them reliant on external resources. In contrast, extended families share responsibilities, reducing burden on parents, but may lead to conflicts and generational gaps. Both structures have trade-offs: nuclear families risk financial strain and emotional burnout, while extended families may face challenges in adapting to rapid social changes. Balancing these aspects is crucial for meeting contemporary needs. The debate highlights the need for flexible family models that combine the strengths of both structures while minimizing their weaknesses. This balance is essential for fostering resilient, supportive, and adaptable family systems in today’s diverse world.

Cultural Variations in Family Structure Preferences

Cultural preferences for family structures vary significantly across societies. In many Western cultures, the nuclear family has historically been idealized, while in Eastern and African societies, extended families are often preferred. Indigenous cultures frequently emphasize collective living arrangements. These differences reflect societal values, economic needs, and historical traditions. For instance, in some Asian cultures, multigenerational households are common, ensuring care for elderly members and preserving family unity. Conversely, Western societies have increasingly embraced diverse family forms, including single-parent and same-sex households. These variations highlight the dynamic nature of family structures, shaped by cultural norms and evolving social values. Understanding these differences is crucial for fostering inclusivity and supporting families in their unique forms. Such diversity underscores the importance of adapting societal systems to accommodate varied family structures.

Challenges Faced by Nuclear Families

Nuclear families often face economic pressures, emotional strain, and isolation due to limited support systems, exacerbating financial and psychological challenges for family members.

Economic Pressures and Financial Strain

Nuclear families often face significant economic challenges, as the financial burden rests solely on the parents. This structure can lead to financial strain, particularly in single-parent households or when incomes are limited. The reliance on fewer wage earners exacerbates the pressure, making it difficult to meet rising living costs. Additionally, the lack of extended family support means nuclear families must independently cover expenses such as childcare, healthcare, and education. This financial strain can lead to stress and reduce the quality of life for family members. The isolation from broader support networks further intensifies these challenges, highlighting the economic vulnerabilities of the nuclear family model. These pressures have become more pronounced in modern societies, where costs of living continue to rise and wages often fail to keep pace.

Emotional and Psychological Strain on Family Members

The nuclear family structure often places significant emotional and psychological burdens on its members. Parents bear the primary responsibility for childcare and household management, leading to stress and burnout. Children in nuclear families may experience pressure to excel academically or socially, as the family’s expectations are concentrated on fewer individuals. The isolation from extended family support can intensify these challenges, leaving members feeling disconnected and overwhelmed. Additionally, the lack of shared responsibilities can create tension within the family, particularly in cases of financial hardship or caregiving for elderly parents. This strain can lead to mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, and may weaken family bonds over time. The emotional toll of relying solely on the nuclear family unit highlights its limitations in providing holistic support for its members.

Lack of Support Systems in Modern Societies

Modern societies often lack robust support systems for nuclear families, exacerbating their challenges. Unlike extended family structures, nuclear families rely heavily on external resources, which are frequently inadequate. Many parents struggle with balancing work and childcare due to insufficient access to affordable childcare services or parental leave policies. Additionally, societal isolation and the decline of close-knit communities leave nuclear families without the emotional and practical support once provided by extended family networks. This isolation intensifies the pressure on individual family members, leading to burnout and stress. Furthermore, the absence of systemic support for single-parent, blended, or same-sex families further marginalizes these households. The lack of comprehensive support systems underscores the limitations of the nuclear family model in modern societies, highlighting the need for more inclusive and equitable structures to help families thrive.

Modern Alternatives to the Nuclear Family

Modern family structures include single-parent, blended, same-sex, and adoptive families, offering diverse alternatives to the traditional nuclear model and reflecting evolving societal values and needs.

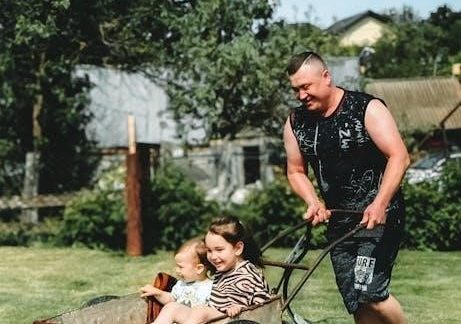

Single-Parent Families and Their Dynamics

Single-parent families, where one parent raises children independently, have become increasingly common due to divorce, loss, or personal choice. These families often face unique challenges, including financial strain and emotional pressure, as the sole caregiver manages responsibilities without a partner. Despite these hurdles, many single parents successfully nurture well-adjusted children, providing love and support comparable to two-parent households. Cedric Traylor, a single father of two, shared his journey, emphasizing the importance of extended family and community support. His household thrives with help from grandparents, siblings, and external networks like teachers and church communities. Single-parent families highlight resilience and adaptability, proving that family dynamics can flourish beyond traditional nuclear structures.

Blended Families and Stepfamilies

Blended families, also known as stepfamilies, involve one or both parents having children from previous relationships. These families often navigate complex dynamics, blending different backgrounds and addressing past relationship challenges. Wendell and Cynthia Booker, for instance, merged their families, with Wendell bringing two sons and Cynthia adding a son and daughter. Initially, they faced “growing pains,” but over time, they built trust and love, creating a cohesive family unit. Cynthia admitted the challenges of becoming a mother of four but emphasized that their bond has strengthened, reducing tensions like “You’re not my real mom or dad” conflicts. Blended families require patience and effort but can thrive, fostering a sense of unity and belonging for all members. Their journey highlights the potential for blended families to overcome initial difficulties and grow into loving, supportive households.

Same-Sex Parent Families and Their Experiences

Amanda and Celeste, a same-sex couple from Louisiana, highlight the challenges and triumphs of same-sex parent families. Raising their daughter, they faced discrimination and societal stigma, particularly within their community. Despite these obstacles, they found strength through their church family, which became a vital support system. Their journey underscores the importance of external support in navigating societal biases. While progress has been made in acceptance, same-sex families often confront legal and social challenges, emphasizing the need for inclusive policies and societal change. These families demonstrate resilience and love, proving that same-sex parents can create stable, nurturing environments for their children. Their experiences call for greater understanding and support to ensure equitable opportunities for all families, regardless of parental orientation.

Adoptive and Foster Families

Adoptive and foster families play a vital role in providing loving homes to children in need. These families expand the traditional nuclear family model by offering care beyond biological ties. Many adoptive parents choose to create families through legal processes, while foster families provide temporary yet critical support. Despite the rewards, these families often face unique challenges, such as helping children heal from past traumas and navigating complex legal systems. Societal support, including financial assistance and counseling, is essential to ensure these families thrive. The experiences of adoptive and foster families highlight the diverse ways love and care can form a family, emphasizing that parenthood is not limited to biology. By embracing these structures, society fosters inclusivity and provides stable environments for children to flourish. Their stories remind us that family is rooted in commitment and love, not just blood ties.

Societal Implications and the Need for Change

The nuclear family model’s decline highlights the need for inclusive policies and support systems to accommodate diverse family structures, fostering a more equitable and adaptive society.

Increased Inclusiveness in Family Definitions

Expanding the definition of family beyond the traditional nuclear model fosters inclusivity, recognizing diverse structures like single-parent, blended, and same-sex families. This shift acknowledges the realities of modern life, where many children thrive in non-traditional settings. By broadening societal expectations, we reduce stigma and promote acceptance, allowing families to feel valued regardless of their composition. Inclusivity also encourages policies that support all family types, addressing unique challenges they face. For instance, single-parent families benefit from financial assistance, while same-sex parents gain legal recognition. This evolution reflects a more compassionate society, where family is defined by love and commitment rather than rigid structures. Cedric Traylor, a single father, highlights the importance of extended and community support, showing how inclusivity strengthens family dynamics and societal bonds.

Better Support Systems for Diverse Families

Modern societies must implement tailored support systems to assist diverse family structures, such as single-parent, blended, and same-sex families. Financial assistance, counseling, and community networks can alleviate challenges like financial strain and emotional stress. For single-parent households, access to childcare subsidies and workplace flexibility is crucial. Blended families benefit from mediation services to navigate complex relationships. Same-sex parents require legal protections and anti-discrimination policies to ensure equality. Adoptive and foster families need resources to address unique challenges, such as post-adoption counseling. By providing these supports, society can empower diverse families to thrive. Cedric Traylor, a single father, emphasizes the importance of community support, highlighting how church and school networks help his family. Such systems foster resilience and inclusivity, ensuring all families receive the help they need to succeed in a changing world.

Improved Outcomes for Children in Diverse Families

Children raised in diverse family structures often benefit from inclusive environments that reduce stigma and promote acceptance. Normalizing non-traditional families can lead to better academic performance and stronger social skills, as children feel more secure and valued. Same-sex parent families, for instance, are shown to foster resilience and emotional well-being in kids, challenging stereotypes. Blended families, despite initial challenges, can provide expanded support networks. Adoptive and foster families offer stable homes, highlighting the importance of love over biological ties. By embracing diversity, society ensures children thrive regardless of family structure. This shift not only enhances individual outcomes but also builds a more compassionate and equitable future for all children. Amanda and Celeste’s experience with church support underscores how community acceptance plays a vital role in their daughter’s positive upbringing.

The nuclear family model is evolving, giving way to diverse structures that prioritize inclusivity and support. Embracing change ensures stronger, more resilient families for future generations.

Reflection on the Nuclear Family’s Impact

The nuclear family, once idealized as the cornerstone of societal stability, has faced growing criticism for its isolating nature and inability to meet modern needs. Critics argue that its rise in the mid-20th century led to a decline in communal support systems, fostering economic strain and emotional pressure on individual households. The shift from extended to nuclear families created a culture of self-sufficiency, often leaving families without a safety net. While it provided a structured environment for child-rearing, its rigidity has been detrimental to many, particularly single parents and marginalized groups. The concept of the nuclear family as a universal ideal has been challenged, prompting calls for more inclusive and adaptable family models that reflect contemporary realities and promote resilience. Its impact underscores the need for evolving family norms to address the complexities of modern life.

The Necessity of Evolving Family Norms

The traditional nuclear family model, rooted in mid-20th-century values, has proven inadequate for many in contemporary society. Rapid social, economic, and cultural changes demand a reevaluation of family structures. The rise of single-parent households, blended families, and same-sex parents highlights the diversity of modern family dynamics. These changes challenge the notion of a one-size-fits-all family model, emphasizing the need for inclusive policies and social acceptance. Evolving family norms would allow for better support systems, addressing financial and emotional challenges faced by diverse family structures. Recognizing and valuing these variations can foster a more inclusive society, ensuring that all families have the resources and recognition they need to thrive in today’s world.

Envisioning the Future of Family Structures

The future of family structures is likely to be characterized by increased diversity and flexibility. As societal norms evolve, the traditional nuclear family model will continue to give way to a broader range of configurations, including single-parent, blended, and same-sex families. There will also be a growing recognition of chosen families and community-based support networks. Policies and cultural attitudes must adapt to these changes, promoting inclusivity and providing resources for all family types. This shift will foster a more compassionate and adaptable society, where no family structure is stigmatized. By embracing this diversity, future generations can benefit from a more supportive and inclusive understanding of what it means to be a family.